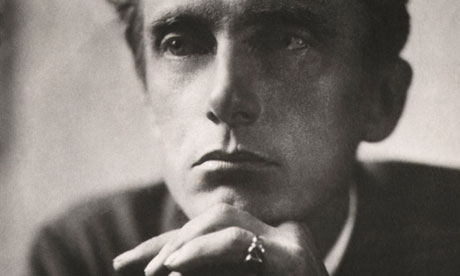

In Pursuit of Spring:Coleridge.

|

| Coleridge or STC. |

Edward Thomas was an admirer and critical student of Wordsworth, Coleridge and the Lyrical Ballads. Surely that volume influenced the thinking, with Frost, that one or the other of them, or both, should write a book on the theory of poetry. He considered Coleridge a great critic. But in In Pursuit of Spring and in his 'A Literary Pilgrim in England ' he insists that Coleridge was a West Country man(originally from Devon) and that all his best work was written there at Nether Stowey in Somerset.

Coleridge had a tremendous benefactor, Thomas Poole, who lived in Nether Stowey in this fine house: the Coleridge's cottage was his and the garden linked with the Poole's.

Poole House, now a B and B.

Poole House, now a B and B.

|

| The Coleridges' cottage, Nether Stowey, Somerset. |

Once Coleridge had moved to the Lakes, away from what Thomas saw as his natural home: 'His notebooks reveal how much he saw, and thought to use in writing, and never did. '

The In Pursuit pages on Coleridge begin with criticism of the early poems, full of Personification of Abstracts in Capital Letters. But Thomas admires him for overcoming the style of his times and forging the new. Edward gets over-excited, he says himself, about the copious honey-suckle around the village which might have served as 'honeydew' for the poet.

He comments many times on Coleridge's use of the terms 'mild' and 'wild' - the ideal has both qualities for him. This is the first time I have read a real close reading of poems by Edward and it is really enlightening, showing the qualities he valued. As we now know that it was in 1913 that he did make one or two attempts at poetry, before the Frost encounter, it must be that he was at some level arguing for his own potential approach.

For example on an early poem, "the uninspired accuracy of 'pink-silver skin' (of a birch tree)".

He comments on several lines which Coleridge cut out - an essential skill in a poet.

He praises the combination of the sensuous and luxurious with 'the quality which responds to ghostliness and to the wildness of Nature, The Keepsake has it perfect, in this picture of a girl,-

In the cool morning twilight, early waked

By her full bosom's joyous restlessness,

Softly she rose, and lightly stole along,

Down the slope coppice to the woodbine bower,

Whose rich flowers, swinging in the morning breeze

Over their dim fast-moving shadows hung,

Making a quiet image of disquiet

In the smooth, scarcely moving river-pool.'

The work of Coleridge's best period unites 'richness and delicacy, sweetness and freshness, sensuousness and wildness, spirit and sense.'

He ends his Coleridge meditation by writing of Christabel and The Ancient Mariner and quoting from the 'May opium dream' of Kubla Khan-

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e'er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon lover!

Of course what we all know about Kubla Khan is the supposed interruption by the Person from Porlock. Edward Thomas doesn't mention it.

Porlock to Nether Stowey is quite a walk - it's now the Coleridge Way of course, taking between 3 and 4 days. Presumably the Person had some means of transport.

.The Walking Holiday comp

.The Walking Holiday compFrom Nether Stowey Edward went on to Holford - almost there at the sea, and with definite signs of spring.

April 1915 was an extraordinarily productive month for Thomas :

Wind and Mist, Lob, Digging, Home, In Memoriam, Health, and half a dozen lesser poems.

I chose In Memoriam(Easter 1915)

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood

This Eastertide call into mind the men,

Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should

Have gathered them and will do never again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Cover artist Marc's pictures on www.artweeks.org/festival/2013/marc-thompson-oas

Blackmore Vale, Dorset

Blackmore Vale, Dorset

William Barnes

William Barnes

Young Emma

Young Emma